The Grand Inquisitor of Toulouse

On women's ceremony, incantation, fatas, divination, and conjuration of herbs

This is an excerpt from a chapter in my unpublished book The Sorcery Charge, Vol XI in my series Secret History of the Witches. It’s one of the most important late medieval texts I’ve found, because it describes (however briefly) pagan observances that women were still carrying out in the early 1300s—and not the “devil-worship” tropes that demonological theologians and inquisitors soon became fixated upon, ever afterward.

Like many Dominican monks of his time, Bernard Gui rose through the ranks of the Inquisition. At the age of 35 he was named Grand Inquisitor of Toulouse, a grisly office he held from 1306 to 1323. Gui is mainly known as a four-star general in the war on heresy. He wrote its first battle plan, a handbook for Inquisitors entitled Practica Inquisitionis Hereticae Pravitatis: a “guide for inquiring into heretical depravity.” (This phrase would be constantly repeated over the next centuries, and in titles of books by other inquisitors such as Bernardo Rategno da Como.

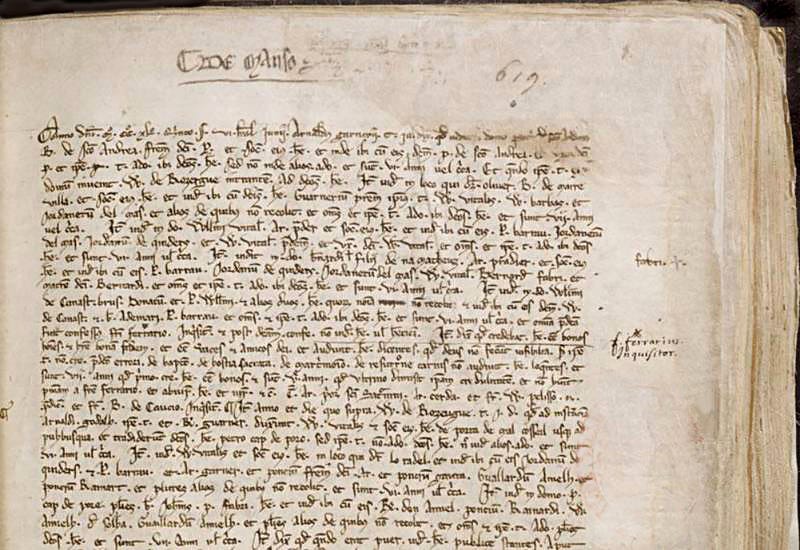

The first interrogatory manual of the medieval Inquisition, the Practica detailed forbidden beliefs, practices and rituals, and set out formulas of abjuration to be repeated by those the Church Militant caused to be tortured into submission. Interrogatory torments administered before the inquisitorial tribunal did not count as punishment, only as the means of extracting "confessions." Official penalties included death, imprisonment, exile, confiscation of property, public humiliation, and enforced pilgrimage to distant sites.

Gui authorizied inquisitors to proceed against heretics, "sorcerers," Jews who were not converted after forced baptisms, and “against all those who oppose themselves to the Office of the Inquisition.” Most of his Practica was aimed against heterodox christians: Cathars, Waldenses, Béguines, and “False Apostles” [Apostolici]. It recognized the upsurge of resistence to the institutional church, which Gui blamed in part on kings interfering with the Inquisition. [Lea Inq II: 104]

Burning Cathars and other “heretics,” a word that once designated schools of thought

Gui’s manual directed special venom against Jewish converts who had returned to their people. This contradicted the clergy's cherished notions of the superiority of their own religion. The inquisitor compared these conversos to “dogs returning to their vomit,” an insult that originated in the pogroms of the First Crusade. When Jews who had been forced into baptism at sword-point refused to actually adopt their oppressors' religion, the chronicler Fruitolf wrote that they returned to Judaism "even as dogs return to their own vomit." [Poliakov I, 51]

Like his colleagues, Gui slandered Judaism as “perfidy" and "intolerable blasphemy." He condemned Hebrew prayerbooks and the "Talmutz," claiming that they contained "imprecations and curses that Jews make against christian people." [Practica, 291] His claim that Jews prayed for god to destroy the Roman faith and all christians was a projection of the priesthood's desire to crush Judaism and the chronic violence that christians committed against Jews.

But inquisitors had also begun to target people who practiced pagan ways, out of their old ancestral heritages. An entire section of the Practica is directed against witches, or as Gui put it, “Sorcerers and diviners and invokers of demons.” This document proves that inquisitors concerned themselves with folk witchcraft at an early date—165 years before the Malleus Maleficarum was published.

Yet historians have repeatedly passed over this significant nugget and ignored its implications. [Lea probably did not recognize the significance of the folkloric references; Russell, 174-5, mentions the Practica briefly, but does not describe its pagan contents, which so happen to refute his thesis that paganism had been fully suppressed by 1000.]

Most historians have accepted the diabolist conception of witches, searching for women who did evil and had intercourse with devils. They tried to match early records with the satanic stereotypes of the mass burnings, and failing to find anything, declared various dates as the definitive horizon of the witch's appearance in Europe. The definition of “witch” they had in mind was the diabolist stereotype. Some categorically declared that no evidence of “true” witchcraft was to be found before 1400, when demonological tracts began to circulate widely, and church officials stepped up frenzied pronouncements against witches.

All this time, these historians ignored (or were ignorant of) crucial testimony that placed witchcraft's roots in folk culture. The evidence was not hidden in some long-lost manuscript, but in the often-cited Practica of Bernard Gui. His description of “sorcerers” contains no mention of devil-sex, or any other inventions of the demonologists. Instead, it catalogs faery beliefs and folk rituals similar to those found in other medieval literature and modern peasant folklore. (I’ve bolded direct quotes.)

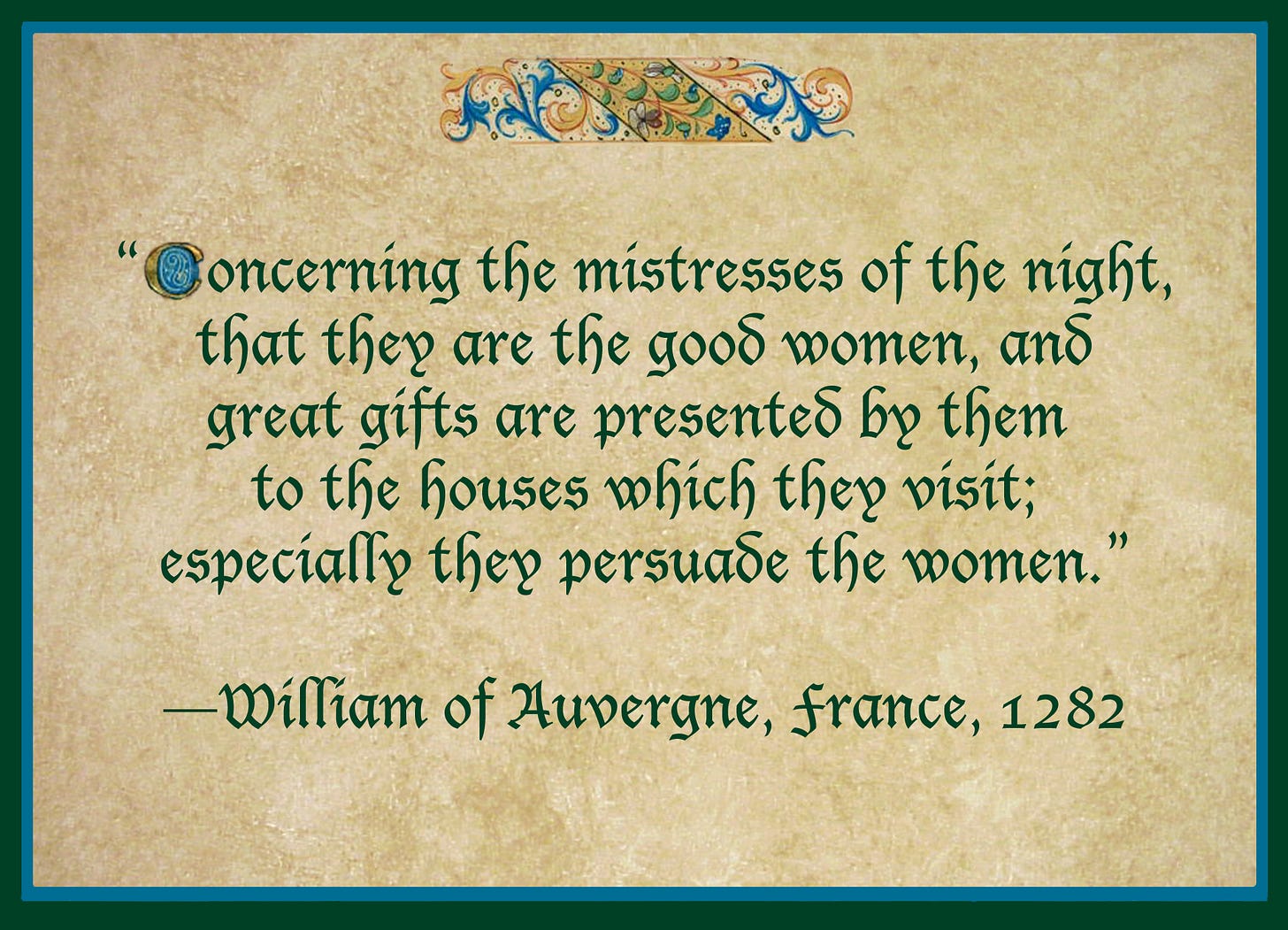

The “sorcerers” of the Practica are not accused of the baby-eating atrocities propagandized by later witch-hunting inquisitors. They follow old pagan beliefs in the fatae: “On the fates of women, called the good ones who, as they say, go by night.” [de fatis mulieribus quas vocant bonas res que, ut dicunt, vadunt de nocte [Practica, 292. An earlier text from bishop Guillaume d’Auvergne alludes to them:

Gui was well aware that the mysteries of the faery faith still held power among the peasantry, especially women. Sorcières who chanted over herbs and cured with conjurations of spirits (fadas or foxileiros in this region) acted as priestesses of ancestral Nature rites that ran deep in the culture of the common people. The challenge they presented to ecclesiastical doctrine was even more broad-based than that posed by the heretics (who were less-numerous but primary targets of the Inquisition in its first century.)

The old spirituality was radically more favorable toward women than institutional christianity. The authoritarian church reserved its own priesthood to a male elite, who received financial and legal benefits from their membership. Even village priests had privileges and immunities from prosecution by the secular power. Clergy, whether adulterers or magicians, were dealt with by the all-male church hierarchy alone, and if they faced any disciplinary action, were treated far more leniently than peasants and fishwives. Their special treatment mirrored similar privileges of aristocrats and men as against commoners and women under the feudal order. Privilege (from Latin “private law”) referred to structural prerogatives and immunities of elite / dominant groups. Some law codes eve bore names like Les Privilèges de Barèges.

Gui's manual gave great weight to the sex of the person who was being cross-examined for “sorcery.” He advised interrogators to consider the quality and condition of the persons, who are not to be interrogated equally or in the same way for everyone, because men are cross-examined in one way and women in another.

This revealing comment stops short of spelling out the difference in how the brotherhood of Inquisitors treated men and women. A look at church precedent offers a dismally uniform bias favoring males over females. But there is more to Gui's emphasis on gender difference: he assumed that his reader knew what acts women performed that men did not do, which were culturally female, handed down and performed by women. The inquisitor broke down “sorcery” into two distinct lists that clarify his meaning. The first sequence concerns witchcraft of the common woman, the second deals with priestly sorcery based on manipulating christian sacraments.

Gui’s description of folk sorcery covers a wide range of beliefs and practices: the prophetic women who go by night, fate-foretelling for infants, ritual chant, conception magic and spells around love and marriage. All of these are explicitly identified as women's realm in medieval sources. The inquisitor's list is fragmented, disjointed, and does not show the relationship between its parts, or the meaning of those parts. Its succinctness reflects Gui’s expectation that the priestly interrogators were familiar with popular divinities and animacy.

Fates and faeries figure prominently in Gui's terse catalog of sorceries. The Practica shows that in Languedoc of 1320, women were carrying out fate-divinations and child-blessing rites on their own, bypassing the priesthood entirely. The common sorcières addressed their incantations to immanent goddesses of destiny, not to a “demon” imagined by the clergy.

Women's rites of birth head the list of “sorceries.” The inquisitor begins by asking what the accused knows, or knew, or did, with regard to the fating or unfating of children or infants. [fatatis seu defatandis, the second word may be better translated as “un-fairying,” as in rites intended to restore a baby for a fairy changeling, as described by an earlier inquistor, Etienne de Bourbon, and portrayed in the 1982 film Sorceress.]

Next the interrogator asks about souls having been lost; this may be the concept of “soul-loss” as a cause of illness, rather than the christian notion of damnation. In the same way, heaven or hell may have had less to do with the condition of the souls of the dead than with the journey of souls to the Otherworld, or ancestor cults of ancient vintage. Communion with the spirits of the dead, and relaying messages from them, was a classic power of the European witch. Peasant tradition held that the dead could be sighted journeying with the Old Goddess on the Ember Nights—or with the Wild Hunt, or the faeries. In the next line, Gui underlines this connection, referring to the fates of women called the good ones, who as they say, go by night (discussed above).

The head inquisitor further asks what the accused knew about or might have done regarding the pronouncement of future events and enchanting or conjuring fruit, herbs, thongs, and other things. The enchantment of thongs (leather strips) refers to the witchcraft of knots. The practice of singing incantations over herbs is attested in the oldest records of pagan observances. The inquisitor lingers on this subject of chants used in healing, and how they are transmitted from woman to woman.

Next he demands from the sorcière the names of those whom she taught chanting or to conjure by chanting, and from whom she learned such incantations for conjurations. The priesthood was determined to systematically track down the teachers and tradition-bearers.

Also forbidden were curing the sick by conjurations or by chanted words, and bringing about impregnation of women. This is conception magic! It’s interesting that no mention is made of contraception or abortion, which were paramount fixations for priestly writers of penitential books from 500-1000. (Their fulminations against women “drinking sterility” and “diabolical potions” branded women who used contraceptives as guilty of “homicide,” which is the likely source for the accusation that witches killed babies.)

Even christianized practices such as collecting herbs with the knee bent and the face toward the east with the lord's prayer are treated as sorcery, along with the combination of pilgrimages and masses and offering candles and giving alms. The peasantry still understood religious acts—christianized or otherwise—as generating power to achieve desired aims. Lighting a candle in a faery grotto might bring about healing or recovery of a loved one. While the “good women” or other divinities smiled on these offerings, theologians considered them heretical attempts to coerce god, even with masses and lord's prayers.

Few peasants were foolhardy enough to admit to the Dominicans that they invoked the spirits of herbs or waters or the Earth. And nothing was more suggestive of witchcraft than discovering hidden facts or manifesting secret things.

Gui lists several sorceries aimed at relations between people. Thieves kept under restraint refers to spells intended to prevent theft (perhaps also to recover lost goods, attested often in European witchcraft literature).

Concord or discord of married couples covers an area of far-reaching concern to women, since both church and state law defined husbands as their lords and masters, who were entitled to beat, rape, and cheat on them, and to squander conjugal property. Witchcraft had long been considered the female remedy to this patriarchal status quo. By the late 1300s, witch prosecutions were increasingly being directed against women for using sorcery to stop their husbands from battering them, or to cause them to return home, or just because.

Out of all the “sorceries” listed in the Practica, only two bear any conceivable relation to harmful maleficia. Discord of married couples might describe a woman’s spell to stop her husband from cheating on her, or to avoid intercourse or battery; or it could refer to magic by jealous or amorous third parties.

Those who give to be consumed hair and fingernails and many other things could refer to harmful sorcery against a person whose trimmings were taken. Such practices are known worldwide—but so is the custom of destroying clippings to prevent others from stealing them in order to cast spells on them. The wording “give to be consumed" suggests that these remnants may have been thrown into a fire to prevent sorcery. Another possibility is that ancestor magic was involved. Inquisitors interrogating Cathars at nearby Pamiers uncovered a custom of cutting a dead person's hair and nails in order to bring happiness into homes. Those same inquisitors also tried four women for invoking the dead. [Cauzons, 333]

Page from the Practica of Bernard Gui

HARMFUL SORCERY

It is crucial to distinguish between maleficia and the vast body of pagan culture, including ancestor veneration, which churchmen insisted on defining as diabolical (Unfortunately countless modern writers and media-makers followed this dogma). Indigenous and other traditional cultures do believe in the possibility of malicious sorcery, and Europe was no exception. But the Catholic priesthood refused to make a distinction between animist healing and malicious sorcery.

Doctrinally, female witchcraft was taboo and male magic was... religion. Under the new order, to act as a priestess meant that a woman could be accused of sorcery. Only males could perform sacramental acts, according to theologians. If a priest’s “magic” fails, he has not failed; it must have been the will of god. In spite of the early medieval stories that describe priests vanquishing Pagan rivals, the Church hedged away from any proofs of effectivenss such as those displayed by shamans. [Herbert Frey, “Religion as an ideology of domination,” in Bak, Janos M. and Gerhard Benecke, Religion and Rural Revolt, Manchester U Press, 1984]

Although doctrine cast the witch as an evil curser, the clergy had long ago evolved its own formulas for cursing—anathemas, excommunications, denial of sacraments. A priest pronouncing these curses supposedly closed off access to the divine and, unless he or another priest lifted them, doomed the victims to eternal hellfire.

The old culture of animacy allowed for the possibility that curses could be laid, that harm could be done to someone through manipulation of symbols or dust from their footprints or a lock of their hair, or even through malevolent looks and speech. It also provided rituals that protected against such action, bringing deities (ancestors, saints, faeries) and natural powers to bear on a person's behalf. Remedies existed in the form of artemisia, south-running water and holy stones, rowan twigs and red thread.

Societies that recognize such powers take into account the possibility of their misuse. Those foolish enough to desecrate medicine arts were capable of using them to do harm through sorcery. The Saami, for instance, considered most noaidis (shamans) to be beneficent but acknowledged occasional cases of evil-doers. [Karsten, 68] The Finns also spoke of "noaidi's arrows" being used to harm.

Some Norse sorcerers sent out spirits called sendingar (“sendings”) or stefnivargar (“directed wolf”) or "mice-wolves," to injure enemies. Others sent spectral milk-hares to bring back cream from other people’s cows. [Craigie] Belief in this magical theft of milk or milk-essence went back centuries and was known across Europe. It was this type of accusation—not diabolism—that dominated peasant thinking when witch-hunting began to penetrate the villages as a tool of communal strife. But the old folk culture held that natural controls deterred magical evildoers. Traditional wisdom warned of a three- or sevenfold return of any wrongful act of sorcery:

The belief among the ancient Irish was, and still is, that a curse once pronounced must fall in some direction. If it has been deserved by him on whom it is pronounced, it will fall upon him sooner or later, but if it has not, then it will return upon the person who pronounced it. They compare it to a wedge with which a woodman cleaveth timber. If it has room to go, it will go, and cleave the wood; but if it has not, it will fly out and strike the woodman himself, who is driving it, between the eyes. [O'Donovan, in Wood-Martin, Pagan Ireland 1895: 149]

Certain power places were resorted to by people who had been injured to cry for retribution. "If a widow or other wronged person made a curse while turning a cursing stone against the sun, it would plague the oppressor's family down seven generations." [Merle Severy, “The Celts: Europe's Founders,” National Geographic, Vol 151, No. 5, 1977] People came to St Brigit's Stone near Lough Macnean in Ireland, a flat-topped boulder with nine dents containing smooth oval stones, to turn the stones while cursing. [Wood-Martin, 150] This custom had become christianized.

St Briget's Stone, Killinagh, near Blacklion, Ireland

A religious context for cursing may seem paradoxical (especially given the unshakably beneficent nature of the goddess Brigid in Irish culture), unless it is understood as an appeal for justice. Its execution is left to the goddess. This concept of appealing to the deity to punish wrongdoers is not foreign to the Hebrew scriptures. And I’ll come back to its wide, if little-discussed, use by the Catholic priesthood below.

But it’s important to understand what has been mostly forgotten since the witch-hunting Terror: that folk culture once had customary ways of resolving fears of sorcery. It was common practice to get a suspected sorcerer to simply say a blessing over the alleged victim. [deWaardt, in G-H/F, 137] Even the demonologist Rémy reports a peasant custom of Lorraine: when someone gets sick from an unknown cause, he goes to the person he blames for it, and get something to eat or drink “in the greatest confidence that it will restore him to health.” [Horsley, 184]

In Germany, Franconian witch belief interpreted witchcraft as a response to wrongs or offenses. It seems that a hex was understood as the negative consequences of bad feeling rather than a conscious act of witchcraft. If someone was afflicted with lice, for example, they should go to the person they believed was responsible for the curse and beg their forgiveness for whatever had offended them—things like the theft of fruit or hay, or allowing their cattle to roam into a neighbor's field. This custom of Abbitte was followed in many cases to try to lift hexes. [Sebald, 77; 104]

This was how the "evil eye" was often interpreted. The life-force of a wronged person could be shaped by their rage and pain without intention to work magical harm. The Italian custom of making "horns,” or “the fig,” was a popular warding gesture that acted as protective magic. Highland Scots used to wind black and white thread around limbs of anyone, human or animal, believed to have suffered the evil eye. [CL Day, 41] These remedies originally were religious and ritual in character. But evil eye beliefs grew deadlier in the witch-hunt era, as poor / disabled / old / women came to be targeted as its probable source. The evil eye became refined into a weapon against female elders, the disabled, and the defiant poor.

People in animist cultures all over the world had traditional methods of recourse against harmful sorcery. But in medieval Europe the remedies themselves had been doctrinally redefined as sorcery, even though the Church's own holy water, incense, and blessed oils grew out of these same animist roots. Priestcraft destroyed traditional distinctions between shamans and cursers, between inspired trance and involuntary possession by malevolent powers.

It was because folk rites and divination and curing were grounded in reverence for goddesses, faeries, Nature spirits, that the Church denied their religious nature. It brought the charge of devil-worship into play. The healers and diviners that people consulted in illness or misfortune were not only outlawed as competitors to the official priesthood, but treated as harm-doers and public enemies. As the witch hunters gained the upper hand, they succeeded in replacing the Old Goddess with the Christian devil.

ECCLESIASTICAL CURSING

The Catholic priesthood devised its own protocols of cursing on religious grounds. In the rite of excommunication, the priest formally cursed those he was casting out of the church, fully believing that he was condemning them to eternal hellfire. Declaring that someone will go to hell or calling down a god's displeasure is, in animist terms, a curse. Many women were burned as witches for predicting much less fearful outcomes. Early church patriarchs were not averse to cursing even christians who disagreed with them. Bishops Cyprian and Gregory of Nazianzus, for example, “called down God’s vengeance against Christians who disobeyed their leaders.” [Lane Fox, 543]

In the rite of excommunication, church officials in full regalia carried candles in procession to the altar, singing softly as a priest called down curses on the excommunicates: "May the wrath and damnation of God Almighty come upon them..." The officiant invoked Mary and the saints, asking that the excommunicates suffer all the plagues of Egypt and the misfortunes of Sodom and Gomorrah:

Their food and drink, their waking and sleeping, shall be damned... They will lose their court cases and their days shall be numbered and evil. They shall forfeit their goods and property to others. Their children shall be orphans and always in want. Fire shall reduce them to penury and wheresoever they shall turn their steps they will be met with abhorrence and shown no pity. [Henningsen, 100-1]

Then the priests consigned their victims to the devil. The assembled clergy all quenched their candles in holy water, saying, "As these candles die in this water, so shall the souls of these rebellious and obstinate people die and be buried in Hell." [Henningsen, 100-1, quoting from the printed Anathema de Valladolid, early 1600s.] More than this, the priesthood demanded that people attend these terrifying displays of wrath and hatred, to make the curse take hold in the collective mind.

The next section of the chapter goes into priestly magicians, whose ceremonial magic invoked angels and devils, and often used consecrated wafers or baptized images of wax or lead. But I’ll end this excerpt here. (Note: full bibliographic information will be provided in the final published form.)

I've tried and failed to get the voice changed to a woman's voice. Doesn't work!